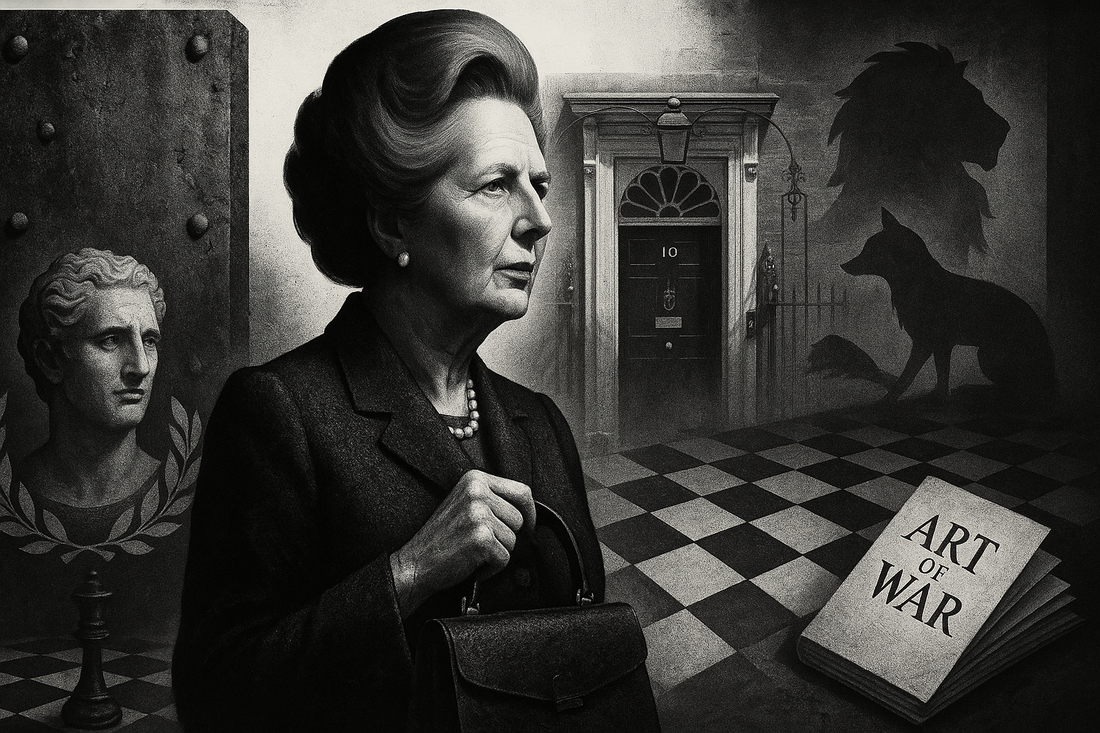

Margaret Thatcher’s Iron Confidence – A Stoic and Strategic Perspective

Former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, aptly nicknamed the “Iron Lady,” projected unwavering confidence and power throughout her leadership.

Introduction: The Iron Lady Unyielding

Margaret Thatcher was not just a prime minister; she was an icon of iron will. In an age of compromise and conciliation, Thatcher strode onto the stage of world politics with the bearing of a battlefield general and the conviction of a philosopher-queen. She earned the moniker “Iron Lady” for her steely resolve – a nickname initially hurled as an insult by the Soviet press but one she gleefully embraced. Leading Britain from 1979 to 1990, Thatcher embodied confidence and power in a way that invites comparison to the great strategists and philosophers of history.

What might the likes of Sun Tzu, Niccolò Machiavelli, or Stoic sages like Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus say about Thatcher’s leadership? In this lighthearted yet insightful exploration, we’ll analyze how Thatcher’s character and leadership style resonated with (and sometimes defied) the teachings of these philosophical heavyweights. Along the way, we’ll glean modern lessons on cultivating self-confidence and personal power – whether you’re leading a company, a political movement, or simply your own life – all delivered in a voice as calm and stoically observant as a Marcus Aurelius meditation (with a dash of dry humor for good measure).

Thatcher once quipped, “Being powerful is like being a lady. If you have to tell people you are, you aren't.”washingtonpost.com. That bit of wisdom could have come straight from a Stoic handbook on humility and confidence. Indeed, it’s a remark as sharp as a sword, neatly slicing through pretension to remind us that true power speaks for itself. In Thatcher’s case, it often roared for itself – through decisive actions, unwavering principles, and an aura that commanded respect without her having to demand it. As we’ll see, Thatcher’s leadership philosophy can be interpreted through ancient lenses: the strategic cunning of Sun Tzu’s Art of War, the pragmatic statecraft of Machiavelli’s The Prince, and the resilient mindset of Stoic philosophers.

So stiffen your upper lip and prepare for a journey through political history and philosophy. We’ll visit the war room of Sun Tzu, walk the corridors of Renaissance power with Machiavelli, and sit by the fireside of Stoic wisdom – all to better understand how Margaret Thatcher exemplified confidence and power. And more importantly, we’ll discover how you can apply these lessons to develop your own unshakable confidence and personal power (with maybe a witty aside or two to keep things light).

The Stoic Soul of Margaret Thatcher

Thatcher’s public persona often seemed as unperturbed as a monk in meditation, no matter what chaos swirled around her. In the face of economic crises, bomb threats, and ferocious political opposition, she showed a remarkable equanimity. It’s no exaggeration to say she demonstrated “amazing stoicism, which saw her through the most harrowing times.” As one close aide recalled, “I told her of a bad opinion poll… She said simply: ‘I took no notice of polls when we were ahead, and I shall take no notice of them now.’”theguardian.com. This almost Zen-like dismissal of public opinion in favor of her long-term vision typifies Thatcher’s Stoic mindset. She was singularly focused on what she believed was right, letting neither hysterical headlines nor panicky polls deter her course.

Stoic philosophers teach that we should distinguish between what we can control and what we cannot. Epictetus, for example, opens his Enchiridion by reminding us that “Some things are in our control and others not… Things in our control are opinion, pursuit, desire, aversion… whatever are our own actions. Things not in our control are body, property, reputation, command… whatever are not our own actions.”classics.mit.edu. By not basing her self-worth on the fickle favor of polls or press, Thatcher intuitively grasped a core Stoic principle: do not hinge your tranquility on external validation. Public opinion and media commentary – much like the weather – were beyond any leader’s control, and fretting over them would be, in Epictetus’s view, a one-way ticket to anxiety. Instead, Thatcher concerned herself with her own actions and decisions (those were in her control) and stayed focused on her policy objectives. The result? A demeanor that often appeared uncannily calm under fire.

This isn’t to say Thatcher didn’t feel pressure or emotion – she was human, after all – but she had a Stoic capacity to master her reactions. Marcus Aurelius could be describing Thatcher’s approach to crises when he wrote: “If thou art pained by any external thing, it is not this thing that disturbs thee, but thy own judgement about it. And it is in thy power to wipe out this judgement now.”classics.mit.edu. Consider the infamous 1984 incident when the IRA bombed the Grand Hotel in Brighton during the Conservative Party conference. The blast tore through her bathroom and nearly killed her and her husband. Thatcher’s response? She insisted on carrying on with the conference schedule at 9:00 am the next morning, as planned, stepping onto the platform to deliver her speech on time “so as to deny the terrorists the satisfaction of disrupting” the democratic processtheguardian.com. This was courage and composure of a high order – the very embodiment of Marcus Aurelius’s counsel to “always easily adapt itself to that which is and is presented” and not be shaken by adversityclassics.mit.edu. Observers were astonished at her steady nerves. In her own deflecting way, she later said it was just determination to not grant “the terrorists their victory.” A Stoic might say she refused to give external evil the power to disturb her inner resolve.

Indeed, Thatcher’s inner citadel – to use a favorite Stoic metaphor – seemed nearly impregnable. Marcus Aurelius wrote that “the mind which is free from passions is a citadel, for man has nothing more secure to which he can fly for refuge”classics.mit.edu. Thatcher was not one to wear her heart on her sleeve in public; she kept her worries and insecurities (if she acknowledged having any) behind the walls of that citadel. There’s a telling anecdote from before she was prime minister: She once rebuked an aide for relentlessly briefing her on negative news, saying, “Don’t you realise that, like other people, I need building up?”theguardian.com. It was a rare glimpse of vulnerability – an admission that even the Iron Lady’s iron can fatigue. But rather than seeking pity, she simply requested encouragement over constant negativity, as any Stoic-in-training might remind themselves to focus on the positive and maintain a resilient mindset.

Thatcher’s emotional discipline was also evident in how she dealt with insults and abuse. And boy, did she face abuse – protest effigies, countless barbs from rivals, even songs celebrating her eventual departure. Yet, she had the ability to tune out the noise. Famously, she often didn’t read the newspapers, relying on her press secretary to filter what she needed to know. She “had the ability, which [her successor] John Major lacked, not to read what journalists wrote about her” and was thus “not disturbed by things, but by the principles and notions” she chose to form about those thingstheguardian.comclassics.mit.edu. In other words, she controlled her interpretation of events and insulated her mind against the daily clamor of criticism. This practice aligns perfectly with Epictetus’s advice: “Men are disturbed, not by things, but by the principles and notions which they form concerning things.”classics.mit.edu. By controlling her own narrative and not internalizing every outside opinion, Thatcher kept her confidence intact. (We might say she was a master of “not giving a darn” in the very Stoic sense.)

Underneath this stoic composure was a fierce determination to turn obstacles into opportunities. Marcus Aurelius compared a resilient mind to a raging fire: throw it more fuel (obstacles, hardship), and it “makes a material for itself out of that which opposes it… as a strong fire consumes obstacles and rises higher by means of this very material.”classics.mit.edu. Thatcher lived this. Every challenge seemed to strengthen her resolve. When economic recession and strikes beset her early years in office, she treated them as fuel to justify and double down on her reforms. When rioters and critics howled, it only convinced her that “if you’re getting flak, you’re over the target.” Her steadfast refusal to perform the politically expedient “U-turn” on policies – encapsulated in her famous declaration, “You turn if you want to. The lady’s not for turning.”washingtonpost.com – showed an almost Stoic obstinacy in following reasoned conviction over popular pressure. (One imagines Marcus Aurelius nodding approvingly at that line; it’s practically an emperor’s way of saying “Stand firm in your principles, come what may.”)

To be sure, Thatcher’s Stoicism had a purpose beyond just personal serenity – it was in service of her political and moral vision. She believed she was doing what was necessary to revive Britain, and that belief was a bedrock she returned to whenever storms raged. In her own words: “I am not a consensus politician. I’m a conviction politician.” Consensus, she felt, was the absence of leadership – “the process of abandoning all beliefs, principles, values, and policies. So it is something in which no one believes and to which no one objects,” she said bluntlywashingtonpost.com. That conviction-oriented mindset is inherently Stoic: it values staying true to one’s principles above the comfort of agreement or the avoidance of conflict. Authenticity, as modern commentators note, was central to her leadership – “True leadership is about authenticity, standing up for principles, even (maybe especially) in the face of strong opposition.”community.nasscom.in. Such a statement could easily describe Marcus Aurelius governing an unruly empire, or Margaret Thatcher facing down a miners’ strike – it fits both.

For the modern reader seeking self-confidence, Thatcher’s stoic streak offers a clear lesson: hold your center. Don’t let external turbulence knock you off course. Whether it’s workplace drama, social media outrage, or personal setbacks, remember that “you have power over your mind – not outside events”, as Marcus Aurelius reputedly said. Realize this, and you will find strength. Thatcher certainly seemed to realize it. Her “mind and soul” were not up for grabs – not by terrorists, not by journalists, not by political opponents. They were hers to command. Cultivating that kind of inner fortress of confidence – one built on values and clear self-direction – is a Stoic practice we can all attempt. You don’t have to agree with all of Thatcher’s policies to admire the unyielding self-assurance with which she carried them out. If you can carry a bit of that iron within you – guided by Stoic wisdom to remain calm, focused, and true to your principles amid life’s tempests – you’ll find your confidence becomes as solid as, well, a bar of Sheffield steel.

Before we move on, it’s worth noting that Stoicism doesn’t mean lack of emotion or empathy. Thatcher herself was often caricatured as cold, but those who knew her recount moments of private compassion and feeling. The key was that she did not allow emotions to govern her decisions. She would listen to her head first, then her heart. This echoes Epictetus’s advice to use reason to govern our impressions, and not act rashly on every feeling. In today’s world, adopting a Stoic pause – a moment of reflection before reacting – can be transformative. Whether you’re dealing with a rude email or a life-altering crisis, channel your inner Iron Lady: square your shoulders, take a deep breath, and decide your response based on principle and purpose, not panic.

In summary, Thatcher’s stoic mindset was a cornerstone of her confidence. She exemplified the power of keeping one’s head when all about are losing theirs. Her legacy urges us to do the same: stand firm in your values, control your reactions, and use challenges as fuel for growth. As a result, you’ll project a presence that others can’t help but respect. In the words of one of her admirers, Thatcher “had backbone”theguardian.com – and in cultivating your own confidence, developing some backbone (fortitude, resilience, and integrity) is a great place to start.

Machiavellian Resolve: Better Feared Than Loved?

If Thatcher was Stoic in personal temperament, in politics she could be strikingly Machiavellian – and we mean that in the renaissance sense, not the pejorative sense. Niccolò Machiavelli, the notorious author of The Prince, advised rulers that “one should wish to be both [loved and feared], but… it is much safer to be feared than loved, when, of the two, either must be dispensed with.”gutenberg.org. Now, Margaret Thatcher did not go around seeking to instill fear in the hearts of the British public (she wasn’t a tyrant), but she certainly did not mind being unpopular. In fact, she famously said, “If you just set out to be liked, you would be prepared to compromise on anything at any time, and you would achieve nothing.” That line could be a direct paraphrase of Machiavelli’s warning that prioritizing being loved leads to ruin. Thatcher’s conviction over consensus ethos meant she was willing to take hard, sometimes painful decisions for the country without flinching at the prospect of blowback. Many did dislike or even loathe her for certain policies – and yet, they respected that she meant what she said and did what she promised. In Machiavellian terms, respect (even tinged with fear) trumped popularity.

Indeed, Machiavelli argued that because “men have less scruple in offending one who is beloved than one who is feared,” a wise ruler should focus on securing obedience and respect; love is fickle, but fear (when not taken to tyrannical extremes) can be dependablegutenberg.org. Thatcher intuitively played by similar rules. She demanded respect and did not lose sleep if “half the nation” vehemently disagreed with her. She once quipped, with trademark dry wit, “I always cheer up immensely if an attack is particularly wounding because I think, well, if they attack one personally, it means they have no political argument left.” In other words, she’d rather be attacked (even hated) for taking a stand than be loved for standing for nothing.

During her tenure, Thatcher handily won three general elections, but she was anything but a “populist.” As one retrospective noted, “Thatcher was never a populist… her deep personal convictions were stronger than her fear of the consequences. She did, however, demand and receive respect from the public.”kingalfredpress.wordpress.com. Here we see the Machiavellian balance: avoid being hated outright, but accept being feared or disliked, so long as you maintain authority and achieve resultsgutenberg.org. Thatcher pushed policies (like austerity measures, union reforms, and the poll tax) that ignited fury in some quarters. She faced miners’ strikes, riots, even an assassination attempt. Yet she pressed on with steely determination. To her supporters, this looked like heroic courage. To her detractors, it looked like stubborn cruelty. Machiavelli would suggest it was likely some of both – but importantly, a leader’s mission was accomplished. Britain’s inflation dropped, the economy revitalized in the mid-1980s, and the power of radical trade unions was curtailed (for better or worse). She delivered results, and as Machiavelli observed, “in the end the arms of others will fall from your back if you are armed with your own resolution.”

One of Machiavelli’s famous pieces of advice to rulers is to be both a fox and a lion: “A prince… ought to choose the fox and the lion; because the lion cannot defend himself against snares and the fox cannot defend himself against wolves. Therefore, it is necessary to be a fox to discover the snares and a lion to terrify the wolves.”gutenberg.org. Margaret Thatcher embodied both of these qualities in her leadership. The “lion” part is easiest to see – her boldness and fearlessness were her calling card. Whether it was facing down the Soviet Union in the Cold War (she forthrightly told Gorbachev she “was not one who was afraid” of engaging in debate), or sending a naval task force 8,000 miles to reclaim the Falkland Islands from Argentina, she acted with the heart of a lioness defending her pride. When Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in 1990, it was Thatcher who famously urged President George H.W. Bush “not to go wobbly”theguardian.com – basically, don’t lose your nerve, stick to your guns. This was pure lion: brash, courageous, and commanding.

But what about the “fox” side of Thatcher? Here was a genteel-looking, well-spoken woman with a handbag, but inside that handbag was often a cunning strategy. She had a talent for political maneuvering and calculation that revealed the fox’s cunning. For instance, after winning the Falklands War and a landslide re-election in 1983, she seized the opportunity to purge or sideline wets and doubters in her Conservative Party, reshaping her Cabinet with loyal Thatcheriteskingalfredpress.wordpress.comkingalfredpress.wordpress.com. That was a shrewd consolidation of power – one Machiavelli might applaud as eliminating potential rivals and strengthening her rule. She could also be calculating in negotiations: during budget meetings with European leaders, she played hardball (“I want my money back!” she demanded regarding Britain’s rebate) and did not hesitate to veto or stall until she got favorable terms. Her tough stance baffled some of her more consensus-oriented peers, but it ultimately forced compromises that benefited the UK. This was the fox sniffing out snares – knowing when others might try to take advantage and cleverly countering it. She also had a knack for rhetorical traps. Her sharp tongue in parliamentary debates often cornered opponents. A famous example: when opposition Labour MP Dennis Healey criticized her economic policy, she responded, “The right honorable gentleman knows that I have the heart of a dove. He just doesn’t know where it’s located.” Confusing Healey for a beat – was that a self-deprecating joke or a backhanded swipe? – as laughter broke out. She would wield humor and sarcasm as subtly as a fox feints to put an opponent off balance.

Thatcher also understood, as Machiavelli advised, the importance of reputation and decisiveness. Machiavelli observed that a prince should avoid being despised; being seen as weak or indecisive breeds contempt and invites challengesgutenberg.org. Thatcher was keenly aware of this. She cultivated an image of strength – not infallibility, but unwavering conviction. When she earned the nickname “Iron Lady” (from a Soviet journalist alarmed by her anti-Communist rhetoric), she immediately embraced it, joking that she gladly accepted an iron compliment. This savvy move turned an intended insult into a personal brand of toughness. From then on, everything about her public presentation reinforced iron solidity: her upright posture, her forceful diction, even the signature handbag she often carried became a symbol of her readiness to smack down bad ideas (“handbagging” entered the British lexicon to mean aggressively rebutting someone). By projecting absolute confidence, she discouraged would-be challengers. Many a Conservative politician who might have liked to usurp her decided not to try, for a long time, simply because Thatcher seemed invincible at the height of her powers. As Machiavelli put it, “Returning to the question of being feared or loved, I come to the conclusion that… a wise prince should establish himself on that which is in his own control… he must endeavour only to avoid hatred.”gutenberg.org. Thatcher established control over her party and the political narrative; she was respected (and yes, somewhat feared) by her colleagues. Crucially, she avoided outright hatred among those whose support she needed – at least until the very end of her tenure, when the poll tax fiasco finally turned many of her own MPs against her. But for over a decade, she balanced on that Machiavellian tightrope, commanding loyalty through a mixture of admiration, fear, and genuine conviction.

It’s worth noting that Machiavelli also advocated for fortuna (fortune) being managed by audacity. He famously likened Fortune to a woman who favors the bold (in rather colorful Renaissance language). Thatcher’s career was nothing if not bold. She took risks that a more timid leader would shirk. The Falklands War was a gamble – success was far from guaranteed against Argentina, yet she acted swiftly and decisively, seizing the initiative (Sun Tzu would approve, but more on him in the next section). Domestically, her free-market reforms were a radical departure from the post-war consensus; she gambled that short-term pain would yield long-term gain. Early on, unemployment soared and riots broke out – the stakes were high, and many thought she’d have to retreat. But Thatcher held firm, trusting her convictions and willing to stake her political capital on them. Fortune, in the end, favored her bold approach: the economy recovered and grew, and she was handsomely re-elected in 1983. Like a true Machiavellian prince, she understood that playing it safe can sometimes be the most dangerous course of all. Better to act decisively and shape events than let events shape you.

For the modern reader, what lessons of Machiavellian confidence can we draw from Thatcher? First, know your values and objectives deeply, so you’re willing to endure unpopularity in service of them. If you constantly need everyone’s approval, you’ll never make tough calls – whether in business or life. As Thatcher showed, trying to please everyone is a recipe for achieving nothing. Sometimes leadership (or personal growth) requires making decisions that others won’t immediately like. Have the courage to be disliked in the short term if you believe in the long term outcome. This isn’t a license to be cruel or insensitive – Machiavelli and Thatcher would both caution against gratuitous meanness that makes you hated. Rather, it’s permission to be firm and make hard choices without seeking validation at every step.

Second, project confidence even if you have doubts internally. Both Machiavelli’s writings and Thatcher’s example suggest that people will follow someone who appears to know where they’re going. Part of Thatcher’s aura was that she almost never publicly second-guessed herself. Even if privately she had moments of uncertainty (which any sensible person does), she put on a brave front. This doesn’t mean you should lie or pretend to be infallible; it means work on your presentation and self-assurance. Stand up straight, speak clearly, own your ideas. If you act like a leader, people are more likely to treat you like one. Remember Thatcher’s “being powerful is like being a lady” quip – if you have to tell people you’re in charge, you aren’t really in charge. So embody it; let your demeanor do the talking.

Third, cultivate both the lion and the fox within. In practical terms: be brave when circumstances demand (don’t shy away from confrontation if it’s important), but also be smart (pick your battles, and use strategy over brute force whenever possible). For example, in a workplace scenario, lion mode might mean standing up to a proposal that you know is wrong for the project, even if it’s unpopular to dissent. Fox mode might mean finding a clever way to present your alternative solution that wins colleagues over, or timing your proposal when it’s likeliest to succeed. Thatcher did both – she roared when necessary, but she also outmaneuvered opponents subtly when she could.

Finally, a Machiavellian tip: don’t back down at the first sign of resistance. If you’ve decided a course is right, stick to it firmly (unless truly convinced otherwise by new evidence). Machiavelli warned that being too changeable makes a ruler appear weak. Thatcher’s near-refusal to do a U-turn (policy reversal) became legendary – and while in reality she did adjust course on minor things, on the big stuff she was immovable. There’s power in that consistency. It builds a reputation that you’re not easily swayed, which can actually deter opposition. People know it’s no use pressuring you because you don’t cave. Of course, one must balance this with listening and learning – blind stubbornness isn’t a virtue. But if after deliberation you believe you’re on the right path, be unwavering. As one of Thatcher’s contemporary admirers put it, “This lady’s not for turning” became a motto of principled steadfastnesswashingtonpost.com. In your own sphere, let others know (through action, not just words) that you stand firm on what matters. It will earn you a certain kind of respect, even from those who initially disagree.

In short, Machiavellian confidence as channeled by Thatcher means bold action, strategic thinking, and a fearless attitude toward public opinion. It’s not about scheming or betrayal (Machiavelli gets a bad rap on that) – it’s about realism in pursuing goals. Thatcher had no illusions that everyone would love her; she chose being effective over being popular. And in the end, many came to admire her authenticity and strength, even if they opposed her policies. She exemplified Machiavelli’s ideal of the leader who is respected and effective, if not universally loved. For anyone looking to lead or simply stand up strongly in their own life, that’s a potent model: prioritize respect over affection, and effectiveness over ego. As Thatcher herself declared, “I am not a consensus politician.” She understood that real leadership sometimes requires forging a path, alone if necessary, until others see the value in following. It’s a lonely road at times, but as she showed, it can change the course of history.

Strategy and the Art of (Political) War

While Thatcher’s steadfastness can be parsed in Stoic or Machiavellian terms, her tactical approach to challenges often brings to mind the ancient Chinese strategist Sun Tzu, author of The Art of War. Politics, after all, was a kind of war for Thatcher – a war of ideologies, a war for Britain’s future, occasionally even a literal war (as in the Falklands). And she proved to be a shrewd general on all these fronts. Let’s see how her methods mirrored Sun Tzu’s timeless advice on strategy, deception, and decisive action.

Sun Tzu’s first lesson is stark: “All warfare is based on deception.”classics.mit.edu This doesn’t mean lying for the sake of it; it means strategy often involves feints, bluffs, and keeping your opponent guessing. Thatcher certainly understood the power of surprise and unpredictability. One could say she deceived Argentina into underestimating her resolve in 1982. At the time, Argentina’s ruling junta doubted Britain would really attempt to retake the Falklands – it seemed logistically crazy, and Britain had been signaling budget cuts to the navy. But when Argentine forces invaded the islands, Thatcher sprung into action with a speed and ferocity that caught them off guard. Within days, she dispatched a naval task force to the South Atlantic. The swiftness of her response was unexpected; it threw the opponent off balance. Sun Tzu writes, “Attack him where he is unprepared, appear where you are not expected.”classics.mit.edu Thatcher’s decision to launch a counter-invasion was precisely that – appearing with a military force where the enemy presumed she either wouldn’t or couldn’t. The result: a swift victory that restored British control. She had, in Sun Tzu’s terms, “balked the enemy’s plans” and shattered their overconfidenceclassics.mit.educlassics.mit.edu.

In domestic politics, Thatcher also employed strategic deception in a subtler way. She concealed her full intentions until the timing was right. For example, prior to tackling the powerful coal miners’ union (the National Union of Mineworkers), she didn’t announce “I’m going to take on the miners” – that would have only united and alerted her adversaries. Instead, she quietly laid the groundwork. Her government stockpiled coal and converted power stations from coal to oil to withstand a major miners’ strike. She appointed ministers prepared to stand firm. Only then, in 1984, when the union called a nationwide strike, was she ready. The confrontation was epic, lasting a year, but Thatcher’s preparation (or you might say, many calculations made in her temple before the battle was foughtclassics.mit.edu) led to victory: the strike collapsed, the unions’ stranglehold was broken, and there were no power blackouts – a stark contrast to the 1970s when strikes had shut down the lights. Sun Tzu could have been nodding along: “The general who wins a battle makes many calculations… in his temple ere the battle is fought. The general who loses a battle makes but few calculations beforehand.”classics.mit.edu. Thatcher calculated extensively. By the time her adversaries realized what she was up to, it was too late. In this sense, Thatcher’s strategic patience and planning echoed Sun Tzu’s counsel that battles are often won before they are fought, through preparation and positioning.

Another Sun Tzu principle is knowing oneself and one’s enemy. “If you know the enemy and know yourself, you need not fear the result of a hundred battles,” he wroteclassics.mit.edu. Did Thatcher practice this? Unquestionably. She had acute self-knowledge: she knew her own mind, her strengths (tenacity, clarity, courage) and her weaknesses (stubbornness, polarizing effect). She famously said, “I’m extraordinarily patient, provided I get my own way in the end.”washingtonpost.com – a tongue-in-cheek self-awareness of her willfulness. She harnessed those traits effectively. And she studied her opponents. Whether the “enemy” was the Soviet Union or the Labour Party or militant trade unions, Thatcher made it her business to understand their motivations, their likely moves, and their pressure points. For instance, she recognized that the Soviet economy was creaking and that a firm Western stance could exploit that; she forged a close alliance with Ronald Reagan and deployed NATO missiles in Europe to counter the Soviet threat, upping the pressure on the Kremlin’s frailties. She also saw an opportunity in the form of Mikhail Gorbachev, a reform-minded Soviet leader, famously pronouncing after meeting him, “We can do business together.” In doing so, she helped open cracks in the Cold War divide. It was strategic insight: know when to be confrontational and when to be diplomatic. Sun Tzu would approve of this flexibility, as he valued winning without fighting when possible, noting “supreme excellence consists in breaking the enemy’s resistance without fighting.”classics.mit.edu. Thatcher’s tough defense posture combined with outreach to Gorbachev arguably contributed to the peaceful end of the Cold War – a victory without a direct military showdown.

On the home front, Thatcher “knew her enemy” in the sense of understanding the public mood and her opponents’ missteps. She had an instinct for the concerns of the average Briton (despite her grand principles). For example, she realized that many working-class Britons aspired to own their home. So she pushed a policy to allow council house (public housing) tenants to buy their homes at a discount. This won over a chunk of the electorate and undermined the opposition, who were then seen as blocking people’s dreams if they objected. It was a strategic flank move – separate the enemy’s forces by appealing to some of their base. Sun Tzu says, “If his forces are united, separate them.”classics.mit.edu. Thatcher’s home-ownership policy did exactly that: it split Labour’s traditional support base, creating “Thatcherites” among blue-collar workers who benefited from her policies. Additionally, her timing in political moves often caught the enemy off guard. She would sometimes call elections at moments advantageous to her (for example, capitalizing on post-Falklands patriotism in 1983). This is classic Sun Tzu: attack when it is least expected.

Thatcher also had a Sun Tzu-like appreciation for the psychological dimension of conflict. Sun Tzu advised, “If your opponent is of choleric temper, seek to irritate him. Pretend to be weak, that he may grow arrogant.”classics.mit.edu. During the miners’ strike, Thatcher refused to engage in personal rhetoric against the miners at first; she let the union leader, Arthur Scargill, rant and rage on television, which eventually turned some public opinion against him (as he appeared extreme and inflexible). She played the long game, presenting herself as regretfully having to uphold the law and keep the country running, while the striking union was depicted as the aggressor causing hardship. In essence, she irritated Scargill by not giving in and by slowly tightening the vise (e.g., sequestering coal stocks), and his temper and overconfidence did the rest, eroding his support. The strategy was to not out-shout him, but to outlast him – knowing that his own anger would alienate moderate miners and the public. It worked: the longer the strike went on, the more the public sided with ending it. By the time it collapsed, Thatcher had not only won the material battle but the narrative battle.

Sun Tzu also emphasizes decisiveness when the moment is right. “When you engage in actual fighting, if victory is long in coming, then men’s weapons will grow dull and their ardor will be damped… There is no instance of a country having benefited from prolonged warfare.” (Art of War, Chapter II)classics.mit.educlassics.mit.edu. Thatcher knew when to strike swiftly. In the Falklands, speed was critical – she didn’t dither with endless diplomacy once she judged that force was necessary. The rapid deployment and assault achieved victory in about ten weeks. In economic policy, too, she front-loaded many painful changes early in her term (knowing her political capital was highest then), rather than dragging it out – a swift shock therapy approach. This is akin to Sun Tzu’s admonition not to protract battles. She often said her philosophy was “Don’t waffle. Decide and do.” That bias for action – once adequately prepared – is a hallmark of good strategy.

For readers today, Sun Tzu’s strategic insights via Thatcher can be translated into personal practice:

-

Plan and prepare before a major “battle” in your life – whether it’s a big presentation, a job interview, or a difficult conversation. Do your homework quietly. Anticipate challenges. As Sun Tzu said, victory often goes to the one who has done more calculations beforehandclassics.mit.edu. Thatcher didn’t walk into confrontations unprepared; neither should you. Confidence is bolstered by preparation. Knowing you’ve laid the groundwork gives you calm and clarity when the conflict actually arises.

-

Use intelligent deception (ethically). This might mean not telegraphing your full plans until the moment to execute. For example, if you’re pitching a new idea at work and anticipate opposition from a certain colleague, maybe have your allies lined up and your data ready, but don’t reveal all your arguments in advance for them to nitpick. Let your opponent underestimate you or misjudge your position, then surprise them with a well-prepared case. It’s not about lying; it’s about timing and presentation – appearing where you’re not expectedclassics.mit.edu. Thatcher often kept her cards close to her chest until she could play a winning hand.

-

Know yourself, know your adversary. This ancient advice is golden in negotiations or disputesclassics.mit.edu. Understand your strengths (and be honest about your weaknesses so you can mitigate them). Understand the other side’s motivations and fears. Thatcher knew, for instance, that the miners’ union relied on solidarity – so she introduced incentives for those who continued working, sowing internal doubt. In a negotiation, if you know the other party actually has a deadline or pressure point, you can leverage that (ethically, again) to find a better solution. And knowing yourself means you won’t commit to battles you can’t handle or that aren’t worth it – choose your conflicts wisely, where you have advantage or righteousness on your side.

-

Maintain the element of surprise. As much as routine and transparency are virtues in many situations, when it comes to competitive scenarios, being predictable is a weakness. Thatcher was anything but predictable to her opponents. Consider adding an element of unpredictability in competitive arenas – e.g., applying an unconventional strategy to a business problem or responding to criticism in a way people don’t expect (like with humor instead of defensiveness). Surprise disarms. It forces others to rethink and often gives you the upper hand.

-

Be decisive at the right time. If you’ve strategized well and a window of opportunity opens – seize it. Sun Tzu valued quick, decisive moves to capitalize on an enemy’s weakness. Procrastination can snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. Thatcher’s bold moves, like privatizing industries quickly or cutting inflation with a shock therapy, were controversial but they prevented drawn-out uncertainty. In our lives, when you know what needs to be done, muster your courage and do it decisively. If you need to cut expenses to get out of debt, better to implement the cuts swiftly rather than agonize through months of half-measures. If you’ve decided to change careers, begin the transition plan and commit to it, rather than waffling indefinitely. Fortune favors the bold, as the saying goes, and as Thatcher’s career illustrates.

In sum, Thatcher’s strategic prowess reflected Sun Tzu’s art of war applied to leadership: careful planning, deception used to gain advantage, deep understanding of friend and foe, and swift decisive action. The result was that she often seemed one step ahead of her adversaries. By studying her example, we too can learn to approach our challenges not just with courage (the lion) and conviction, but with strategy and cunning (the fox). Confidence is not just about believing in yourself, but also about having a game plan to win. Thatcher had both – an unshakeable belief in her mission and a clear-eyed plan to achieve it. That’s a potent combination we can all aspire to in pursuing our own victories, great or small.

Modern Lessons: Developing Your Own Iron Will

We’ve journeyed with Margaret Thatcher through the lens of Stoicism, Machiavellian realpolitik, and Sun Tzu’s strategy. Now the question is: How can you apply these principles to develop greater self-confidence and personal power in your own arena – be it business, politics, or everyday life? Let’s distill some practical lessons from the Iron Lady’s playbook (with philosophical footnotes attached, of course):

1. Stand by Your Principles – and Don’t Fear Dissent:

Thatcher’s confidence sprang from clarity of conviction. She knew what she believed, and she stood by it even under fire. In our lives, confidence is deeply rooted in living by our values. Define what you truly care about – your “north star.” It could be integrity, creativity, justice, or any guiding principle. Once you have that, let it guide your decisions. Not everyone will agree with you – and that’s okay. As Thatcher showed, trying to please everyone is a trap. Epictetus might remind you that reputation is not fully in your control, only your own actions areclassics.mit.edu. So do what you feel is right, and accept that some people may criticize. If your goal was noble and your conscience is clear, you’ll find a quiet confidence in knowing you didn’t betray your values for approval. Over time, people respect someone who stands for something, even if they initially oppose it. True confidence isn’t cockiness; it’s quiet self-assurance that you’re being authentic and principled. Thatcher’s life was a case study in conviction – she invites us to find the courage of our own convictions.

2. Cultivate Resilience – Embrace the “Obstacle is the Way” Mindset:

Thatcher endured setbacks and storms but famously said, “You may have to fight a battle more than once to win it.” Resilience is confidence’s best friend. When things go wrong – and they will, at times – resist the urge to see yourself as a victim. Instead, channel that Stoic alchemy of turning obstacles into fuelclassics.mit.edu. Ask: What can I learn from this? How can this challenge strengthen me or improve my strategy? Thatcher’s setbacks (early unpopularity, economic woes, even being ousted in the end) did not break her spirit; she kept her head high and often rebounded in new ways (she remained an influential voice even after leaving office). To apply this: next time you face a personal or professional failure, take a page from Marcus Aurelius – remind yourself “It’s not what happens to you, but how you react that matters” (a sentiment often attributed to Epictetus). Focus on what you can control – your response, your next moveclassics.mit.edu. Every comeback builds confidence, proving to yourself that you can survive difficulty. Like tempered steel, you become stronger with each trial. Eventually, the world throws less at you, seeing that you are not easily shaken – much as terrorists failed to shake Thatcher’s resolve by bombing her conferencetheguardian.com. Be the one who stands back up every time – there’s quiet power in that.

3. Prepare and Practice – Confidence Through Competence:

One source of Thatcher’s confident aura was that she was always prepared. Colleagues marveled (and sometimes winced) at how thoroughly she mastered her briefs and could grill experts with off-the-wall questionstheguardian.comtheguardian.com. There’s a straightforward lesson: do your homework. Whatever field you’re in, know your stuff. If you have a big meeting, prepare answers to potential questions (and maybe a few “off-the-wall” ones to challenge yourself). If you’re negotiating, research the facts and figures inside out. Competence breeds confidence. Sun Tzu’s many calculations before battleclassics.mit.edu translate to modern life as study, practice, rehearse. Athletes visualize and drill so that on game day, they perform with assurance. Similarly, Thatcher’s preparation allowed her to walk into high-stakes situations radiating confidence – she earned that poise through work. This is excellent news for those of us not born brimming with confidence: you can work your way into confidence. The better you become at something, the more confident you will feel doing it. It’s cause and effect. So adopt a growth mindset and keep honing your skills. Over time, your knowledge and experience form a bedrock that even impostor syndrome can’t easily crack.

4. Communicate Assertively and Authentically:

Thatcher’s voice (both literal and metaphorical) was a key part of her power. She famously took voice lessons to deepen and steady her tone, giving her speech extra authority. More importantly, she spoke her mind. She didn’t beat around the bush or rely on vague platitudes. You knew where she stood. To apply this, practice assertive communication. That means stating your thoughts and needs clearly and respectfully, without undue apology or aggression. Instead of saying, “Um, I was just thinking maybe we could possibly consider another approach?”, say “I propose we consider an alternative approach, because X.” Own your ideas. Marcus Aurelius advised speaking “both simply and directly, with an ethos of justice and modesty”classics.mit.educlassics.mit.edu – a good recipe for communication. Thatcher was direct (sometimes to a fault), but you can temper assertiveness with stoic calm and politeness. The effect is that people take you seriously. They may not always agree, but they’ll know you mean what you say. Additionally, be authentic: don’t try to imitate someone else’s style (Machiavelli cautioned against trying to be someone you’re not, noting that authenticity inspires trustcommunity.nasscom.incommunity.nasscom.in). Thatcher’s unique combination of ladylike poise and fierce conviction was her – she made no attempt to be “one of the boys” or anyone else. Likewise, find your own voice. If you’re naturally witty, use humor (Thatcher herself had a sardonic wit that disarmed critics at times). If you’re thoughtful, speak with that thoughtfulness. Authenticity, as we saw, is central to true leadershipcommunity.nasscom.in. When people sense you are real, they’re more inclined to trust and follow, which in turn boosts your confidence in leading.

5. Don’t Take Everything Personally – Keep the Goal in Focus:

Margaret Thatcher developed a remarkably thick skin. She had to, given the level of vitriol aimed her way. One of her secrets was not internalizing insults. She once paraphrased the old saying: “It’s a sign of spring when the cuckoos sing; it’s a sign of success when they sling mud at you.” In other words, if you’re getting flak, you’re likely doing something significant. This perspective is very much in line with Stoic thinking and even a dash of Zen humor. Try not to take criticism or opposition too personally. Often, resistance or criticism says more about the other person or about the circumstances than about your worth. Epictetus would advise: if someone criticizes you and it’s true, then it’s not an insult but a learning opportunity; if it’s false, why let it upset you unjustly? Thatcher exemplified this by filtering the noise – having her press secretary give her summary reports instead of reading hate-filled editorial pagestheguardian.com. You might not have a press secretary, but you can consciously limit your exposure to negativity when you know it’s not constructive. Don’t doomscroll nasty comments or obsess over one detractor’s opinion. Stay focused on your mission. Machiavelli noted that great leaders often have to endure being misunderstood or maligned in the short termgutenberg.org. Keep your eye on the prize – whether that’s completing a project, winning a campaign, or simply self-improvement. By keeping a higher perspective, you won’t be derailed by every slur or setback. Thatcher’s ability to not personalize every attack gave her tremendous freedom to act confidently. You can gain a slice of that freedom by reminding yourself: “It’s not about me, it’s about the goal.” This detachment, interestingly, makes you more effective and often eventually earns the respect (or at least quietude) of former critics.

6. Balance the Lion and the Fox – Be Courageous, But Also Clever:

Sometimes confidence means charging forward (lion mode), and sometimes it means laying a trap or choosing a smart detour (fox mode). Thatcher’s legacy teaches that both modes have their place. In practical terms, being courageous might mean finally asking for that raise, or saying no to a commitment that’s overwhelming you, or standing up for someone being treated unfairly – despite fear of consequences. Being clever might mean finding a compromise that saves face for all parties, or negotiating in a way where everyone feels like a winner, or even quietly solving a problem before it becomes a crisis. The key is situational awareness. Sun Tzu wrote, “According as circumstances are favorable, one should modify one's plans.”classics.mit.edu. In your journey to greater confidence, learn to read situations and apply the appropriate tactic. Thatcher could bulldoze through a wall when needed, but she could also take a step back and find a different route when direct force wasn’t viable. Confidence is not stubborn blindness; it’s adaptable and pragmatic. Know that assertiveness does not mean aggressiveness 100% of the time. Sometimes a confident person yields strategically to win later, much like Thatcher would sometimes retreat on a minor issue to preserve capital for a bigger battle. By blending bravery with brains, you’ll find you not only feel more confident, but you actually achieve better outcomes – which further reinforces confidence in a virtuous cycle.

7. Lead by Example – and Don’t Flaunt Power:

Thatcher gave orders, certainly, but she also worked tirelessly herself – often outworking her aides (to their chagrin) by staying up late drafting speeches or poring over detailstheguardian.com. Her work ethic and discipline set a tone. She lived her famous dictum, “I do not know anyone who has got to the top without hard work.” In your context, if you’re in a leadership role (at work or even as a parent or community leader), confidence comes from doing what you expect others to do, walking the talk. People are far more likely to rally behind someone who pulls their weight and then some. And as they rally, your position is strengthened, boosting your confidence further. At the same time, heed Thatcher’s (and Lao Tzu’s, funnily enough) advice about power: if you have to constantly remind people you’re in charge, you’re not truly in chargewashingtonpost.comcommunity.nasscom.in. Confidence is quiet. Avoid micromanaging or overly touting your title or authority. Instead, focus on earning respect through competence and integrity. Thatcher didn’t demand respect – she commanded it by her presence and actions. In everyday terms, that might mean taking responsibility when things go wrong (rather than blaming others), sharing credit when things go right, and treating others with consistency and fairness. Those behaviors mark you as a natural leader and imbue you with a steady, unshakable confidence that isn’t dependent on positional power but on personal character.

By adopting these lessons, you can start to forge your own “iron will.” Remember, confidence is not a static trait, bestowed on a lucky few. It’s a skill and attitude that anyone can develop with practice and mindfulness. Margaret Thatcher’s journey from a grocer’s daughter in a small town to a dominant world leader is evidence of that. She crafted herself into the formidable figure we remember – through study, determination, and an unwavering belief in her values and capabilities. You can do the same in your sphere. You might not be running a country (if you are, cheers to you!), but you are the prime minister of your own life, so to speak. You get to set the agenda, choose the principles, and lead the charge.

And if doubt ever creeps in, perhaps imagine Maggie Thatcher, Sun Tzu, Machiavelli, and Marcus Aurelius assembled in your kitchen as a kind of quirky confidence advisory panel. Marcus strokes his beard and reminds you to center yourself and not be ruled by fear. Sun Tzu points at the chessboard of life and nudges you to think a few moves ahead. Machiavelli arches an eyebrow and says, “Don’t worry if they don’t like you, just get the job done (ethically).” And Thatcher herself, with a fond pat of her handbag, simply says, “Don’t wobble, dear.” Then you straighten your back, smile, and carry on – unbowed, unbent, and unafraid.

Conclusion: Forging Your Own Path with Confidence and Purpose

Margaret Thatcher’s legacy is a study in the power of self-belief, strategic acumen, and principled leadership. Through the interpretive lens of Sun Tzu, Machiavelli, and the Stoics, we see that her brand of confidence was not mystical or innate – it was earned and cultivated. She demonstrated how a person can shape themselves with ideas and discipline: she fused the Stoic resilience of Marcus Aurelius, the pragmatic savvy of Machiavelli, and the strategic boldness of Sun Tzu into a formidable personal alloy. The good news for us is that these qualities are not reserved for historical titans alone. We can each apply these timeless principles to become more confident and effective in our own lives.

In the end, Thatcher exemplified a sort of philosopher-warrior mindset: deeply reflective about her purpose yet utterly unflinching in action. She showed that humor and sternness, grace and grit, intellect and instinct can all co-exist in one individual – making her, in the words of Shakespeare, a woman “of infinite variety.” And while you may not agree with every decision she made, there’s no denying she lived on her own terms and left an indelible mark on the world.

So as you step forward on your own path, take heart from the Iron Lady’s example. Be stoic in setbacks, strategic in challenges, and stout-hearted in pursuing what matters. Face life with a twinkle in your eye and steel in your spine. Develop the quiet confidence that comes from preparation and principle. And whenever you need a boost, recall Thatcher’s immortal words and the philosophy behind them. If critics doubt you or if you doubt yourself, you can always channel that dry Thatcherite retort: “You turn if you want to.” As for you? This person’s not for turning – not aside from your goals, not away from your values. Keep going, keep growing, and let your confidence shine not in words of self-praise but in the courage of your actions.

In the battle of life, that is how you embody true power – with a gentle smile, a firm resolve, and perhaps, every now and then, a witty remark about walking on water just to remind the world that you, like Margaret Thatcher, mean business.

Sources:

-

Michael Portillo, The Guardian: Personal reflections on Thatcher’s courage, stoicism, and leadership styletheguardian.comtheguardian.comtheguardian.comtheguardian.com.

-

Marcus Aurelius, Meditations: Insights on controlling one’s reactions and turning obstacles into fuelclassics.mit.educlassics.mit.edu.

-

Epictetus, Enchiridion: Stoic teachings on focusing on what is in our control and not being disturbed by externalsclassics.mit.educlassics.mit.edu.

-

Niccolò Machiavelli, The Prince: Notable advice on whether it’s better to be feared or loved and the use of cunning and strengthgutenberg.orggutenberg.orggutenberg.org.

-

Sun Tzu, The Art of War: Strategies on deception, knowing one’s enemy, and the importance of planningclassics.mit.educlassics.mit.educlassics.mit.edu.

-

Margaret Thatcher quotes (via Washington Post and others): On power and leadership (“being powerful is like being a lady…”washingtonpost.com, “the lady’s not for turning”washingtonpost.com, etc.), highlighting her own words that reflect these philosophies.

-

“LeaderTalk” article referencing Thatcher: Emphasizes authenticity and principle in leadershipcommunity.nasscom.in.

-

The Legacy of Margaret Thatcher, King Alfred Press: Discusses Thatcher’s convictions over populism and the respect she commandedkingalfredpress.wordpress.com.

Through these sources and Thatcher’s story, we see a cohesive picture: confidence and power are as much an art as a science, a mindset as much as a skillset. Thatcher mastered that art in her context. Now, armed with these insights, you can begin mastering it in yours – with perhaps a bit more humor and wisdom on your side, courtesy of the giants who traveled with us on this analytical journey. Go forth and lead your life with iron confidence and golden purpose. Good luck – or as the Iron Lady might say with a smile, “Now stop whining and get on with it.”