The Power of Perception: Wearing the Mask of Virtue

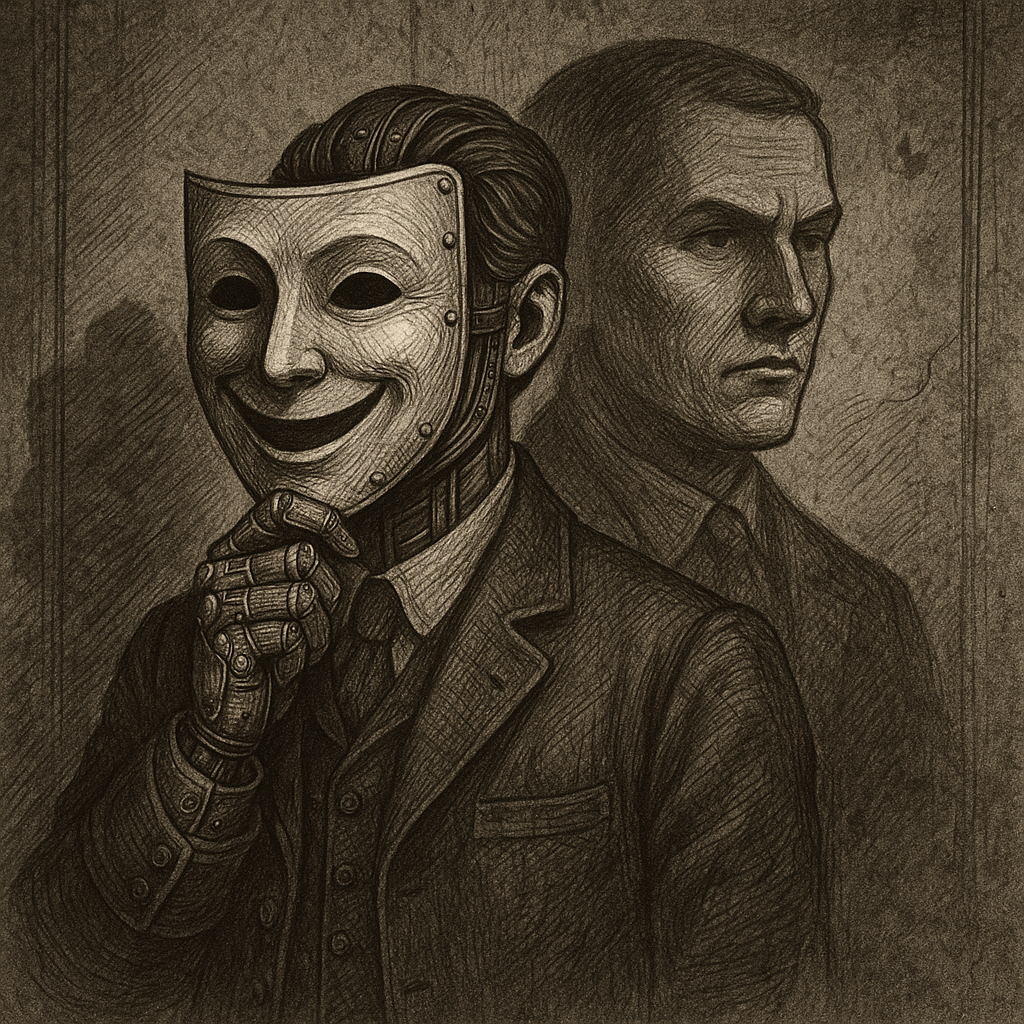

Introduction – The Theater of Influence: All the world is a stage, and upon it we are all players presenting ourselves in curated guise. No one understood this better than I, Niccolò Machiavelli. In politics, in business, in social life, people judge first by appearances – by what their eyes see and their ears hear – and only a rare, penetrating few discern the reality beneath. Thus, to command influence, one must learn the art of perception management: to appear honest, confident, and benevolent, even if in pursuit of one’s pragmatic ends one must occasionally act otherwise. “Every one sees what you appear to be, few feel what you are,” I wroteen.m.wikisource.org. In modern terms, this means your reputation – the image you project – often outweighs your true intentions or character in shaping others’ behavior toward you. This is not a cynical condemnation of humanity but a useful insight: you have the power to shape how others perceive you, and by extension, how they treat you. By wearing the mask of virtue, you gain trust and cooperation; by controlling your narrative, you wield influence over hearts and minds. The Machiavellian guide to modern life thus insists: cultivate a sterling image while keeping your strategy close to the chest. In a digital age of curated social media lives and corporate branding, this principle rings truer than ever.

Machiavelli’s Insight – Appear Virtuous, Be Strategic: In Chapter 18 of The Prince, I addressed this directly: “It is not necessary for a prince to possess all the good qualities [virtues], but it is indispensable to appear to have them”en.m.wikisource.org. I even went so far as to say a prince should utter nothing that is not imbued with righteousness, mercy, integrity, and piety – in other words, maintain the mask of virtue publiclyen.m.wikisource.org. Why did I counsel this? Because I observed that people in general “judge more by their eyes than by their hands,” meaning they trust what they see over the abstract truthen.m.wikisource.org. A ruler who publicly exemplifies generosity, fairness, and devoutness will win the affection and confidence of his subjects, even if behind closed doors he must make hard decisions contrary to those virtues. Conversely, a ruler (or person) who openly displays vice or cruelty – even if rarely – will quickly earn fear or scorn, undermining their influence. Thus, I argued, if you must act against virtue, do so secretly; but in public, always shine as an example of virtue. In plain language for today: manage your brand. Make sure that what people associate with your name is positive and admirable, even if your private maneuvers are more complex.

Now, some might object: is this not deception or hypocrisy? Indeed, it is a form of strategic deception, but one that acknowledges a reality of social dynamics. Machiavelli is not urging immorality for immorality’s sake; rather, I recognized that unfiltered honesty can be a liability in a world where others may not have your best interests at heart. By wearing the mask of virtue, you protect yourself and your mission. Importantly, I did not say virtues are bad – I said using virtue as a tool is often essential. If you can truly have the virtues and still succeed, wonderful! But if you cannot always practice them (and reality often impedes pure virtue), at least make sure you maintain the reputation of having them.

Historical Parallel – The Mask in Action: Consider the example of Octavian Caesar (Augustus), the first emperor of Rome. In his rise to power, Octavian engaged in brutal proscriptions (political purges) and outmaneuvered rivals with great cunning – acts hardly in line with “virtue.” However, he very carefully cultivated an image of himself as the restorer of the Republic’s peace and traditional values. He commissioned poets like Virgil to sing of Rome’s renewed golden age under his guiding hand, posed as a humble servant of the Senate, and publicly adhered to moral propriety (encouraging marriage, punishing adultery, etc.). The Roman people and aristocracy, weary from civil war, saw Octavian’s mask of virtue and gladly accepted his rule, hailing him as Augustus (the revered one). Underneath, he was creating an autocracy, but thanks to his managed image, he faced remarkably little resistance and enjoyed popular legitimacy. Octavian didn’t rely solely on fear or force; he solidified power through perception. By the time many Romans realized the Republic had given way to Empire, it didn’t matter – Augustus was beloved and respected. This is Machiavellian theater par excellence. In modern terms, Octavian was a master of personal branding and PR, aligning his public persona with the values of his target audience while executing a shrewd consolidation of power behind the scenes.

Modern Example – The Friendly Tech Mogul: Fast-forward to the present. Look at Bill Gates as a case study. In the 1990s, Gates (leading Microsoft) had a reputation among competitors as extremely tough, even ruthless – Microsoft engaged in business practices that landed it in antitrust trials, accused of using monopoly power to crush rivals (some might say these were Machiavellian tactics in business). Yet, what about Gates’s public image today? He is widely seen as a benevolent philanthropist, a genial, nerdy billionaire giving away his fortune to fight disease and climate change. This transformation is no accident of fate; it is a carefully cultivated persona shift. Gates stepped down from day-to-day Microsoft roles and increased the visibility of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. Interviews show him as thoughtful, compassionate, slightly awkward but deeply earnest about helping humanity. Most of the world that doesn’t follow tech history closely might never guess that in his competitive heyday he was feared by many in Silicon Valley. By wearing the mask of virtue – in this case, genuine charitable work combined with savvy publicity – Gates has largely shed old negative perceptions. Microsoft’s past aggressive strategies are now a footnote compared to Gates’s current identity as a global do-gooder. This shift has allowed Gates to wield soft power (in global health, education, etc.) far beyond what a “ruthless tycoon” image would permit. Whether one believes his intentions are 100% altruistic or not, the result is clear: the perception of Bill Gates is overwhelmingly positive and trustworthy, which opens doors and ears for his influence worldwide.

The Lesson – Control Your Narrative: From these examples and countless others, the lesson emerges: you must control your own narrative, or others will craft one for you – often to your detriment. Humans are quick to label and pigeonhole. If you don’t consciously present the qualities you want to be known for, you might accidentally display something unflattering and that will stick. Machiavelli would say: do not leave your reputation to chance. Construct it. Think of it as your personal armor – a gleaming suit that dazzles observers so they do not see any weaknesses underneath. This means paying attention to the little signals you send: your words, your deeds (especially the visible ones), even your attire and associations. They all tell a story about you. Choose that story with care. If you want to be seen as competent and reliable, for instance, always meet your deadlines publicly, even if behind the scenes you had to scramble frantically – show the calm swan above water, paddling furiously beneath where no one sees. If you want to be seen as generous and kind, make sure your acts of generosity are noticed (don’t assume people will find out on their own). This might sound manipulative, but consider: if you truly did a kind thing but no one knows, it unfortunately does little to build your reputation for kindness. Machiavelli would nudge you to ensure it becomes known, albeit gracefully (no one likes blatant self-promotion, so perhaps you mention it humbly or others are invited to witness it). On the flip side, if you must do something that might tarnish your image – say, a difficult firing of an employee or a harsh critique that’s necessary – try to do it away from the spotlight or couch it in justifiable terms. Control how the story is told: “I had to let them go because it was in the best interest of the team’s morale and productivity, and I did it respectfully with a generous severance”. This way, you manage potential negative fallout.

Beware the Pitfalls – Sincerity vs. Cynicism: Now, one might ask: is it not exhausting or unethical to live behind a mask? Here I must clarify: Machiavelli never advocated outright fraud for malicious ends. The “mask of virtue” is not an excuse to betray all virtue with impunity. In fact, the best scenario is when you actually possess many of the virtues you project – then the mask is simply emphasizing the best side of you. The mask is needed because no one is perfectly virtuous at all times, and because public perception often needs a simplified, idealized version of reality. Think of a parent who feels anger or frustration but presents a calm, loving face to a child to not scare them – is that hypocritical? Or is it wise and benevolent? It is the latter. Similarly, a leader may have doubts and fears in private, but publicly exudes confidence to inspire the team. That’s wearing a mask, yes, but in service of a greater good. The danger lies in believing your own act to the point of folly, or using it purely to deceive for selfish gain. Machiavelli warned that a prince should actually cultivate virtuous qualities, but with the ability to “learn how not to be good” when compelleden.m.wikisource.orgen.m.wikisource.org. In modern life, that means: strive to be good, but when you must deviate (and life will put you in positions where strict honesty or generosity might be harmful to you or your mission), do so discreetly and never let it mar the overall virtuous impression you give. Hypocrisy is a vice only if it’s transparent. If done skillfully, it is not called hypocrisy at all, but diplomacy, tact, professionalism. Most people accept that social graces involve a bit of acting. We smile and say “I’m fine” even on rough days – that’s a mask to smooth interactions. Machiavelli simply advises to take this natural social lubricant and weaponize it for your success: consciously embody the best virtues outwardly.

Practical Tactics – Becoming the Persona: How can you do this concretely? First, decide on the key virtues or qualities you want to be associated with. Is it integrity? Intelligence? Compassion? Strength? Charisma? Each field or situation might demand emphasis on different virtues. A politician might choose “honesty, patriotism, and concern for the common man.” A business leader might choose “innovation, reliability, and social responsibility.” An individual in a friend group might pick “loyalty and fun-loving positivity.” Once identified, consistently broadcast those qualities in your behavior and communications. If loyalty is your chosen virtue, be seen going out of your way to stand by friends or colleagues. If innovation, frequently share new ideas or creative solutions (and let others know you’re working on novel projects). Repetition and consistency forge the link in observers’ minds: Ah, that person is always [virtue]. Weave these displays naturally – it should feel authentic even if calculated.

Next, minimize public evidence of behaviors that contradict your chosen virtues. We are all multi-faceted; you might be loyal but sometimes you can’t help someone, or you value honesty but there are truths you must withhold. The key is: do not let those instances define you publicly. For example, if generosity is part of your persona, avoid public quibbling over small expenses or being seen as stingy – even if privately you are frugal, outwardly maybe treat people occasionally or let someone else take the last slice of cake. It’s about creating a consistent narrative.

Also, leverage the tools of modern perception management: social media and networking. Curate your online presence to reflect your desired image. People often believe what they see on someone’s LinkedIn, Facebook, or Instagram as if it’s the whole truth. Use that: highlight the activities, endorsements, and associations that bolster your virtuous persona. Delete or downplay content that clashes with it. This isn’t being fake; consider it storytelling. You are the protagonist of your own story, so tell it the way that best advances your goals and aligns with your values.

Analogy – The Mask and the Mirror: Think of your external persona as a beautifully crafted mask. On the inside of the mask (facing you) is a mirror. When you wear it, you see both the mask and yourself. This means as you project the qualities, you are also reminding yourself to live up to them. Over time, the more you “wear” the mask of, say, confidence, the more you truly internalize confidence. Many a shy person has become a great leader by acting confident until it became real. This is the positive side of the Machiavellian approach: by consciously embodying virtue, you might actually cultivate it genuinely. The mask, in an ideal scenario, merges with your face; the public virtue and private virtue become one. But even if they don’t fully merge, the mask at least ensures that your occasional weaknesses or vices do not become common knowledge to be used against you.

Cautionary Tale – Leaders Who Dropped the Mask: Consider moments when public figures accidentally revealed traits that contrasted with their carefully built image – the “hot mic” gaffes or leaked emails that show a cynicism or bias contradicting their stated principles. Such incidents can be devastating precisely because they yank away the mask and show the less savory reality. The public feels betrayed (“He wasn’t who we thought he was!”) and trust evaporates. Machiavelli would stress: guard against such revelations vigilantly. Control information about you. If you hold opinions or plans that would shock others, discuss them only with your most trusted confidants in secure settings. Always assume that anything you say or write could become public – a good Machiavellian practice – and phrase even your private communications in a way that, if exposed, can be explained without destroying your virtue image. This sounds paranoid, but in an age of data breaches and smartphone videos, it’s prudent. An example: if you must fire someone for poor performance, do not write an email calling them “lazy and useless” (even if you feel that in frustration); instead write “unfortunately they were unable to meet the requirements of the role” – a professional wording you’d not be ashamed of on the front page of a newspaper. Always maintain the tone of the persona you present, even when you think no one is looking. That way, if the curtain is pulled back, there’s no hideous monster behind – maybe just a less saintly, more human version of the virtuous persona, which people can forgive.

Beyond Self – Perception of Your Work and Ideas: This principle also applies to framing your projects and ideas. A mediocre plan sold with brilliant optics often beats a good plan presented poorly. Machiavelli noted that results matter – the “vulgar” (common people) judge by outcomes and appearances, not inner intentionsen.m.wikisource.orgen.m.wikisource.org. So if you have a great idea, package it in attractive virtue. For instance, if you run a business making a necessary but boring product, cast your company’s mission in noble terms (“we are dedicated to improving everyday life for ordinary families” – see how that sounds virtuous compared to “we sell cheap hardware”). The substance can remain the same, but the perception elevates it. Politicians do this incessantly: every bill, however mundane, is given a high-sounding name (who would oppose a “Patriot Act” or an “Affordable Care Act” based on title?). You, in your own sphere, should do similarly: garb your actions in honorable language and rationale. Not only does this win external support, it also keeps your own purpose focused. A Machiavellian actor operates with intention; controlling perception requires clarity of what you want others to believe. So articulate it often, to them and yourself.

Charisma and Imagery – The Virtù of Presence: Part of managing perception is also consciously displaying confidence and ease. I wrote that a prince must learn how to “feign and dissemble” at timesen.m.wikisource.org – essentially, to act. In modern settings, this might be akin to emotional intelligence and charisma. Even if you feel angry, scared, or insecure, often the strategic move is to project calm, courage, and assurance. This is wearing the mask of composure. People take cues from your external demeanor. If you come across as in control, they grant you more influence. If your face shows panic, they panic too or lose faith in you. Think of a doctor who calmly informs a patient of a serious diagnosis versus one who seems flustered; the calm one instills more confidence (even if internally, they both feel the gravity). So, practice mastering your expressions and tone. The mirror inside the mask can help here: watch yourself in literal mirrors or recordings, see if your body language exudes the virtues you want to showcase (confidence, openness, determination). Politicians hire media coaches for this reason – to train every gesture and inflection to align with the desired image. You might not need to go to that extreme, but awareness is key. Present the best version of yourself at critical moments, just as an actor gives their best performance on stage, saving their fatigue or personal troubles for after the show.

Ethical Considerations – Using the Mask for Good: You might wonder, is it ethical to consciously manipulate perception? There’s a positive way to view it: by managing how others see you, you can lead them more effectively and reduce conflicts. If your team sees you as caring and competent, they will worry less and work better – that’s good for everyone. If your community trusts you as a person of integrity, they are more likely to follow your lead on beneficial initiatives. In contrast, if you selfishly mislead – say, pretend to care just to exploit – that is a darker use of the mask and can backfire badly when discovered. Machiavelli didn’t explicitly moralize on this; he observed what works. But even he noted that great pretenders and dissemblers like Pope Alexander VI succeeded in their aims precisely because people believed them despite their notorious track recorden.m.wikisource.org. The takeaway: if you choose to use the mask, use it with purpose and caution. The mask can become a prison if your entire life is a lie; ideally, it is more like a knight’s armor – something you don in the public arena for protection and advantage, and remove in private with those closest to you. Indeed, everyone should have a small circle where the mask can be set aside (trusted family, dear friends) – even Machiavellian princes had confidants. This keeps you sane and grounded.

Conclusion – Master of Appearances, Master of Destiny: In today’s society of relentless media and fleeting attention, Machiavelli’s lesson on perception is not just relevant; it’s indispensable. Cultivate your image as carefully as a gardener tends prized roses. Prune away the negatives, water the positives, present the bouquet to the world. Recognize that perception drives reality in many ways. A talented person ignored will languish, while a less talented but well-perceived person rises – unless the talented one learns to shine their own spotlight. So do not shy from a bit of self-promotion and stagecraft. Machiavelli serves as your stage director, whispering from the wings: “Smile now, speak with conviction, that’s it – appear the part and you become the part.” The world reacts to you largely based on what you present. By wearing the mask of virtue – whether that be honesty, courage, kindness, or all of the above – you encourage people to treat you as virtuous, which in turn can make your path smoother to actually achieving virtuous outcomes. After all, if everyone believes you are honest, they’ll entrust you with opportunities where you can do genuine good (just be sure not to betray that trust recklessly).

Finally, remember that reputation is hard-won and easily lost. Guard it as you would guard your treasure. Every action either polishes or tarnishes your mask. When in doubt, err on the side of protecting your good name. As the old saying (often attributed to my contemporary, Ovid) goes, “A good reputation is more valuable than money.” Machiavelli would agree: with a good reputation, you can achieve things money alone can’t. People will lend you support, credit, loyalty. Perception becomes reality – you are treated as capable, and thus you can exercise capability. You are trusted, and thus given the chance to justify trust. All because of the careful maintenance of an image.

In the grand tapestry of influence, perception is the golden thread. Weave it wisely, and the garment of your life’s work will be admired by all. Let that mask of virtue smile upon the world, and behind it, let your astute mind work freely to secure the success, stability, and happiness you seek – a happiness made easier when one is favored and not maligned by society. Master appearances, and you master fate. That is the power of perception.